Fujii started learning shogi at the age of 5. When he entered the first grade he began attending a shogi class where children aspiring to become professional players study. Those wishing to turn pro usually join Shorei-kai, a society under the Japan Shogi Association aimed at training young aspiring players, and must achieve a sufficient number of wins. If one attains the fourth dan (rank) before turning 26, one can become a pro player. Professionals are ranked between fourth dan, the lowest, and ninth dan, the highest.

Fujii became the youngest professional shogi player ever at the age of 14 years and two months last October, breaking the record set by Hifumi Kato, a ninth-dan player, 62 years ago. He also became the fifth player to turn professional while still a junior high school student. Two months later, he beat Kato — now 77 — in his professional debut. As if symbolizing the arrival of a new epoch, Kato ended his career spanning 63 years last week after suffering a loss to 23-year-old fourth-dan Satoshi Takano.

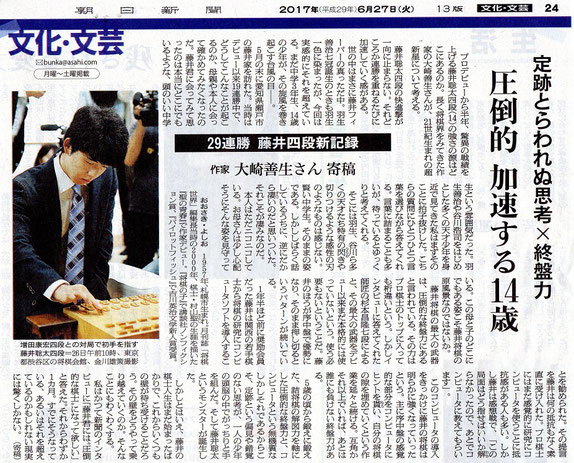

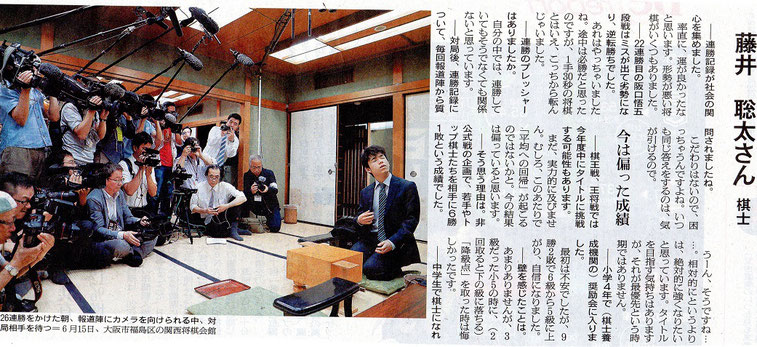

Fujii clinched his 29th straight win on Monday by defeating fellow fourth-dan Yasuhiro Masuda, age 19, in the prestigious Ryuo Championship finals, meaning that he will move on to challenge Ryuo title holder Akira Watanabe, who is 33 years old. The new record came 30 years after Hiroshi Kamiya achieved a streak of 28 wins in 1987.

It is probably the first time since Yoshiharu Habu made a clean sweep of all seven top shogi titles at the same time in 1996 that a single player has caused a nationwide sensation. Many people must be surprised by Fujii’s mental strength. He has repeatedly said that he plays shogi with a relaxed attitude and is not conscious of winning games. That is easier said than done.

Behind his strength is his conscientious effort. He has solved more than 10,000 tsume shogi (composed shogi problems) to hone his ability to “read” the situation on the board and predict what developments the next move will produce. A professional player is said to be able to foresee several dozen, and sometimes, several hundred, developments that the next one move will bring about. Fujii also uses computer software to study the game.

A computer shogi program beat a professional player for the first time in 2013. The superiority of artificial intelligence over humans in the world of shogi became clear when the PONANZA program defeated Amahiko Sato, an eight-dan master, 2-0 in April and May. Even in the world of the ancient Chinese board game of go, where it was thought to be much harder to develop software that can beat top human players, Google’s artificial intelligence program AlphaGo stunned players and fans by trouncing Ke Jie of China, the world’s top player, 3-0 in a five-game contest last month. But Fujii’s use of shogi software serves as a good example of how to best utilize AI to improve a player’s skills in the game. One likely effect of his use of software may be his excellent power of concentration.

Last year, suspicions arose that Hiroyuki Miura, a ninth-dan player, relied on shogi software while playing a match — which resulted in his brief suspension from the game. Although he was eventually cleared of the allegation, a dark cloud hung over the world of shogi. Fujii’s stunning performance brings a ray of hope and encouragement to the shogi community. He has reminded people of the drama of a shogi game — how a judgment a player makes in an extremely tense situation can affect the eventual outcome of the match — a process that moves people watching the drama unfold. As people’s excitement over the performance of the 14-year-old prodigy shows, the superiority of artificial intelligence in the world of shogi will not render the game obsolete or irrelevant.